We have a house full of little known history. By sharing a house and land, several early Concord African American families were able to support themselves and to lead independent lives.

The stories of the occupants of The Robbins House reveal the ways in which the first generations of free Concord African Americans pursued independence and contributed to the antislavery movement and abolitionist causes.

The Robbins House

CONCORD’S AFRICAN AMERICAN HISTORY

1823 – present

PATHWAYS TO INDEPENDENCE

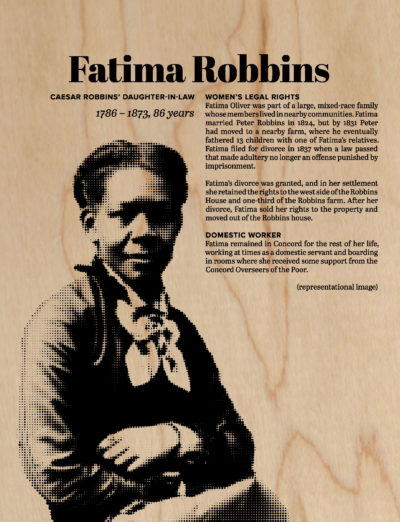

This 544-square-foot house, built in the early 1820s, was originally located on an isolated farm overlooking the Great Meadows along the Concord River. The first two families who lived here were descendants of Caesar Robbins, a Revolutionary War Patriot. In 1823, Caesar’s son Peter Robbins purchased the new two-room house and over 13 acres for $260. Peter and his wife Fatima resided in the west side of the house; Peter’s sister, Susan, her husband Jack Garrison, and their children occupied the east side. Peter Hutchinson, Fatima’s relative, bought the house in 1852. He and his large family were the last to live in this house on the farm.

POWER OF SELF-DETERMINATION

In 2010, the house was saved from demolition, moved here, and restored. Today, the Robbins house embodies the determination of Caesar Robbins and his family to support themselves on the land and to shape their own destinies as free men and women—and serves to inspire conversations about race and social justice issues.

(Herbert Gleason, “Field of Rye,” courtesy Concord Free Public Library.)

Meet the Residents

The Robbins House embodies the determination of people like Caesar Robbins to support themselves on the land and to shape their own destinies as free men and women.

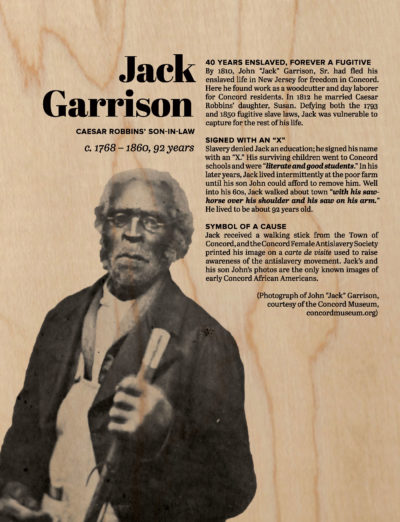

Meet the residents of the Robbins House – their stories reveal the little known African American history of Concord and its regional and national importance. (Portraits of the residents are representational – images courtesy of Prints & Photographs Division – The Library of Congress.)

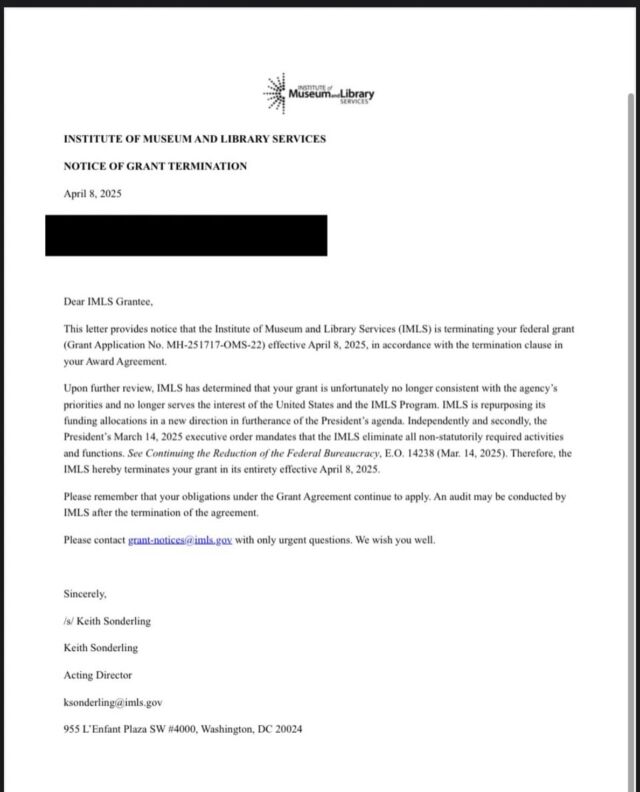

This project was made possible by the Institute of Museum and Library Services Grant # MH-00-17-0030

Caesar Robbins

Peter Robbins

Susan Garrison

Jack Garrison

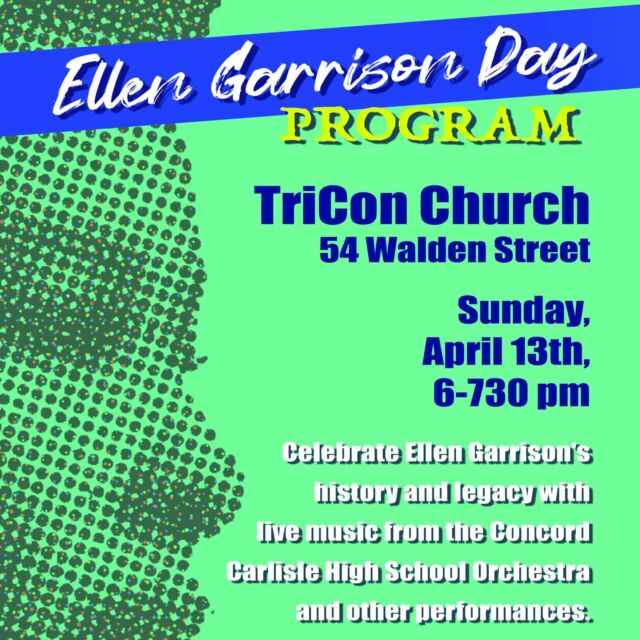

Ellen Garrison

Peter Hutchinson

Fatima Robbins

Meet more Early Concord Residents and Visitors

Frederick Douglass, Harriet Tubman, and Sojourner Truth and John Brown all spoke against slavery while visiting Concord.

Mary Merrick Brooks

A slave-owner’s daughter, Mary Merrick Brooks was one of Concord’s leading white abolitionists.

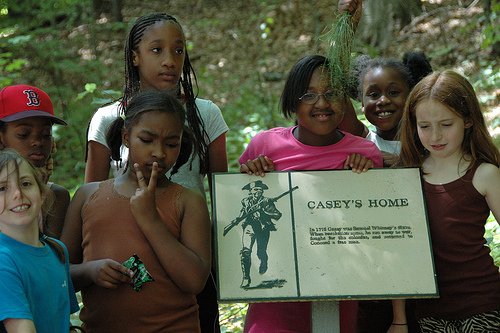

Case Whitney

Case(y) was enslaved to Samuel Whitney, Patriot muster master, at the Wayside. A few yards down from the Wayside, Case’s plaque is a reminder today of one of Concord’s courageous self-emancipated slaves: “In 1775 Casey was Samuel Whitney’s enslaved person. When the Revolutionary War came, he ran away to war, fighting for the colonies, and returned to Concord a free man.”

Ralph Waldo Emerson

Ralph Waldo Emerson was slow to take on anti-slavery activism. In 1844, he and his wife signed a petition 1. Against slavery, 2.Against discrimination, but not against 3. De-segregating the railroads. By 1851, however, Emerson presented an impassioned speech to the citizens of Concord against the Fugitive Slave Law. By 1859, Emerson assisted John Brown, leader of the Harper’s Ferry Raid.

Colonel James Barrett

Colonel James Barrett was like many other wealthy and titled Concord men in the 1700s in that he owned slaves, including a young man named Philip who is listed in a 1775 militia roll call. For a school assignment, one of Barrett’s sons drew up a mock bill of sale in which he imagined selling Philip to a Cambridge resident.

Brister and Fenda Freeman

After 25 years of enslavement, Brister Freeman became the second former enslaved person to own land in Concord. Brister’s Hill is named after the area where he and another former enslaved person purchased an acre of “old field.” Brister and his wife Fenda, who told fortunes, had three children. Brister worked as a day laborer and endured frequent harassment from local residents and officials. Impressed by what Brister had been able to accomplish in such a hostile environment, Thoreau compares him in Walden to Scipio Africanus, the great Roman general.

Zilpha (or Zipha) White

Formerly an enslaved woman, Zilpah White lived in a one-room house on the common land that bordered Walden Road. She made a living spinning flax into linen fibers. In Walden, Thoreau notes that, like other former enslaved persons, she too was harassed. He describes her living conditions as “somewhat inhumane.” And yet her ability to provide for herself at a time when few if any other Concord women lived alone was a great accomplishment.

Thomas and Jennie Dugan

Thomas Dugan was a self-emancipated African American from Virginia. He was the third former enslaved person to own land in Concord. He and his first wife Catherine had five children. When Catherine died, Thomas married Jennie Parker of Acton, who may have been born in Africa, and after whom Nut Meadow Brook was renamed Jennie Dugan’s Brook, due to her and her husband’s contributions to the community. Thomas and Jennie Dugan had three children. One of them, Elisha Dugan, lost his father’s land and subsequently lived in the woods. He was memorialized by Thoreau in his poem The Old Marlborough Road. Thomas Dugan introduced the rye cradle to Concord and taught local farmers to graft apple trees.

Cato and Phyllis Ingraham

When local squire Duncan Ingraham moved to Medford in 1795, his man Cato asked if he could marry a local (currently or formerly) enslaved person named Phyllis and bring her along. Duncan replied that Cato could marry but only if he stayed behind in Concord, severed his ties with his master, and sought no further financial assistance from him. Cato chose Phyllis over a secure financial future and Duncan thus abandoned him to his freedom, providing him with only a small house and permission to live in it on an acre of sandy land in Walden Woods. In Walden, Thoreau bemoans Cato’s early death. He and his family died of diseases associated with malnutrition. Thoreau was inspired to live in Walden Woods due to these courageous individuals.

Uncover Concord’s Black History

Did you know that there are many houses in Concord that were stops on the Underground Railroad? That the Alcotts, Thoreaus and Emersons were all antislavery activists? That the sisters, aunts, mothers and wives of those famous Transcendentalists formed the “Concord Female Anti-Slavery Society”? That Harriet Tubman, Frederick Douglass, Lewis Hayden, William Lloyd Garrison and John Brown all visited and spoke in Concord? That some of our streets are named after black residents, such as Peter Hutchinson, Jennie Dugan and Brister Freeman?

Parts of Concord’s history are either forgotten or buried

Each day visitors and residents pass by the following places:

- Walden Pond (home to slavery survivors Brister Freeman, Cato Ingraham and Zilpha White)

- Brister’s Hill Road and Brister’s Spring, named after Brister Freeman

- Sanborn Middle School, named after Abolitionist Franklin Sanborn, one of John Brown’s Secret Six supporters

- The First Parish Church, were Frederick Douglass and Harriet Tubman spoke against, and John Brown protested slavery.

- Peter’s Path and Spring, named after Peter Hutchinson, the last resident of color to live in The Robbins House.

- Caesar’s Wood, named after slavery survivor and Revolutionary War veteran Caesar Robbins

- Jenny Dugan Road & Spring, named after the local wife of self-emancipated Thomas Dugan, and mother of 54th Regiment Civil War soldier George Dugan.

- Several homes in Concord that served to shelter self-emancipated enslaved people fleeing the south as Underground Railroad sites.

And never learned that slavery existed in Concord and the North, or that:

- Jack Garrison, a self-emancipated enslaved man and original resident of the Robbins House, has a walking stick and carte de visite showcased in the Concord Museum.

- John Jack, likely Concord’s first enslaved man to gain his freedom and purchase land and a house, has a world famous epitaph on his headstone in the Hill Burying Ground.

- Susan Garrison, original resident of the Robbins House, was a founding member of the Concord Female Antislavery Society, along with Lidian Emerson and the Thoreau women.

- Susan’s daughter Ellen Garrison Jackson went south after the Civil War to teach newly freed African Americans, and had the Baltimore Railroad stationmaster arrested for throwing her out of the ladies waiting room – a test of the 1866 Civil Rights Act.

- Mary Rice, a Concord kindergarten teacher with a classroom in Wright’s Tavern, sent a petition signed by over 195 children to President Lincoln asking that he “free all the little slave children in this world,” and received a direct response.

- Shadrick Minkins, the first self-emancipated enslaved man to be captured in Boston after the 1850 Fugitive Slave Law, was rescued and driven to Concord by Lewis Hayden, and sheltered in the Bigelow house across from the Concord Main Library.

TIMELINE

1725 –1st record of Blacks in Concord (some freed before the 1780 law)

1765 – Concord begins to oppose slavery

1775 – Concord men gather for the Revolution – Battle at the Old North Bridge (war 1775-1783)

1780 – Mass. Constitution with Bill of Rights – Slaves freed Post Revolution – Concord’s agrarian period

1835 – Massachusetts Antislavery Society founded

1837 – Concord Female Antislavery Society founded

1844 – 1st time Ralph Waldo Emerson speaks in public about slavery, at Henry David Thoreau’s Walden Pond cabin.

1850 – Fugitive Slave Law – establishing Concord’s role in the underground railroad

1861 – Civil War (to 1865)

1862 – DC Compensated Emancipation Act paid out $1M to 3,100 slaves owners to set their enslaved workers free over 9 months

1863 – Emancipation Proclamation (applying only to states seceded from the union) – didn’t immediately free any enslaved African Americans – changed the character of the war.

1864 – Mary Rice letter to and from Lincoln (petition from 195 – 350 students to free enslaved children)

1865 – Thirteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution abolished slavery and involuntary servitude.

Online Teaching Tool and Resource

Concord: Its Black History 1636-1860, was written Barbara K. Elliott and Janet W. Jones of the Concord Public Schools in 1976. We plan to update and rewrite this as an online teaching tool and resource.

CONCORD: ITS BLACK HISTORY

CONCORD: ITS BLACK HISTORY

1636 — 1860

Prepared by

Barbara K. Elliot and Janet W. Jones

Illustrated by

Laraine Armenti and Carolyn King

A book written for children to learn about the history of black people who lived, worked, and died in Concord, Massachusetts from 1636 to 1860.

Soft cover illustrated book, 8.75″ x 6″

132 pages, Copyright 1976